Years ago when I first started at Relativity, we had an amazing engineering leader named Security Bill.

Security Bill taught us a lot. For instance, he knew our most likely breach scenario was low-tech: someone tailgating into our office behind a polite door-holder, then sticking a USB into an unlocked machine. So Bill set out to create a new norm. Everyone would badge into every door, every time. If you were walking back from lunch with your best work friend, and the CEO happened to be walking behind you? All three must badge in, one at a time. If the CEO was distracted, late, in a rush, and forgot to swipe his badge, it was your duty to remind him he needed badge in. Even if you were just an intern. This would usually mean stopping right in the doorway and physically standing in his way. It was a hard norm to enact in a company of a few hundred people, but Security Bill was a patient and persuasive man. Leadership bought in first, and slowly the new norm stuck. Within a couple of months, the whole company was badging in, and holding each other accountable.

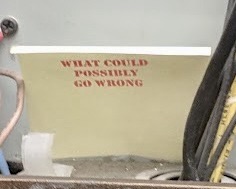

But the badge norm protected against only the first half of the threat, and still wasn’t foolproof. So Bill also had a custom stamp with a red ink pad. He carried the stamp and ink in a little case, along with a fresh set of yellow sticky notes. If you stood up for a drink or bathroom break and didn’t lock your computer, and Security Bill happened by, you’d return to find a sticky note on your monitor. On the yellow paper would a red stamp that read in block letters “WHAT’S COULD POSSIBLY GO WRONG?”

And Security Bill was always willing to describe for you what could possibly go wrong.

Security Bill taught us other things, beyond how to have a security mindset. I was once asked in a meeting to do something that was outside my skill set and comfort zone. I said something like, “I’m not very technical, I don’t think I can own this.” Bill encouraged me to try, and offered to help if I got stuck.

After the meeting, he pulled me aside and told me a story. “When I was young, my parents sent me to work on my uncle’s farm for a summer. For the first two weeks, every day I was asked to do something I had never done before. What would he have said to me if I’d told him, ‘I’m not very agricultural, I don’t think I can do this.’ Some things are hard. But we’re smart, and we figure them out.”

Security Bill created a permanent security mindset at Relativity. Throughout his career he also helped me and hundreds of others learn how to build a culture of excellence; how to fight an uphill battle and win; when to be a careful thinker, and when to jump in and figure it out.